Thank you for your interest in adopting a galgo (Spanish bred greyhound).

Please read through this information and when you feel ready, kindly complete the Homing Questionnaire and then we will be able to start the adoption process by arranging a home visit.

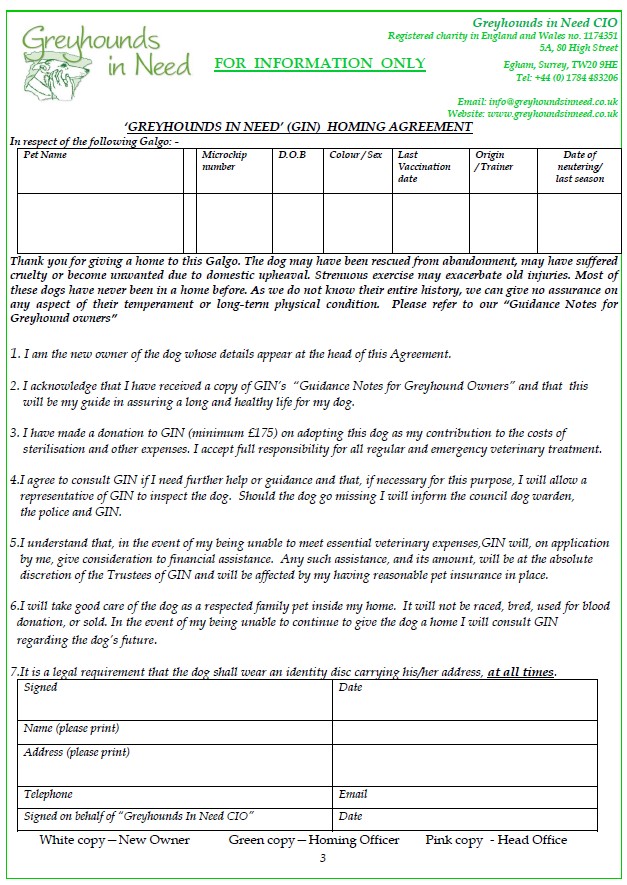

Please do not complete the Homing Agreement yet – this is for your information only at this stage.

All of the galgos we rescue are tested for Leishmaniasis, Babesiosis, Heartworm, and Ehrlichiosis which are diseases that occur in Mediterranean countries but are not commonly known or endemic in the UK. The tests we undertake are to ascertain whether an individual galgo is currently infected with this disease but diagnosis can be challenging and latent infections can be difficult to diagnose.

Details of these diseases can be found in our Information library and we include a technical paper below which could be of interest to your veterinary surgeon.

We feel it is fair to point out that in line with other welfare groups who do similar work, we would appreciate a donation of at least £175 on the adoption of one of our galgos, to enable us to continue to take in, maintain and prepare for adoption (with vaccination, dental cleaning, sterilization, etc) more dogs in need.

With best wishes, The Trustees of Greyhounds in Need

_____________________________________

HOMING QUESTIONNAIRE

The Homing Agreement below is for information only at this stage.

REHOMING A GALGO

The Galgos (breed name galgo español) are Spanish bred greyhounds used widely by hunters in the rural areas of Spain, for coursing the hare with betting but the season is only 4 months after which time they are abandoned or brutally killed. Many have not been handled kindly, some have suffered victimisation in overcrowded shelters in Spain, making them wary of other dogs, and some need gentle socialisation and a lot of reassurance that they are never going to be hungry or hurt again. They were rescued in the first place by volunteers who themselves suffer the hostility of their own countrymen for showing such concern and care.

Galgos for homing in the UK – a question often asked is “how does the adoption process work”? On receipt of a completed questionnaire, our homing officer will contact you and arrange for a home check to take place. It is only after a successful home check that “would be” adopters are told which dogs are still available, and a visit to the kennels can be arranged.

Throughout the time from initial contact to adoption many questions are asked and advice sought, especially by “first-timers”. Some of the points raised are:

Toilet Training: Dogs straight from kennels are not toilet trained, but it shouldn’t really take long if handled with sensitivity. They want to get it right but when they first arrive home they don’t know where the back door is and might have a few accidents while learning.

Living with other pets: Many Galgos will accept cats and other small animals with no problem at all. Many others will accept and adapt to living with cats, etc. quickly once they have learned their boundaries. It is usually down to careful introduction initially and owners carefully supervising “dog and cat together time”. This is one of the reasons why when you collect your new dog you are given a muzzle in addition to a collar and lead.

Living with babies and children: There is no reason why dogs and babies should not co-exist happily and safely. If you are expecting a new baby start training your dog to stay out of any “no go” areas of the house as early as possible. Introduce new items such as cots, car seats, prams etc as early as possible in order to get the dog used to them. It also helps if you can get a recording of baby sounds so that when the baby arrives the dog will not find

it strange. NEVER leave a baby alone with a dog however much you think you can trust the dog. ALWAYS praise and reward your dog when it behaves well around the baby so it will accept the baby is nice to have around. As children grow they should be taught to respect the dog, never touch it suddenly, especially if it is asleep, not to pull it’s tail or poke little fingers in eyes and always to allow it to have it’s own space. Galgos often become a child’s best friend.

Generally: A greyhound collar should be put on high up the neck at the narrowest point and fit snugly. It is a good idea to have a house collar which remains on at all times—inside and outside complete with ID tag which has your name, address and telephone number. It is a legal requirement for an ID tag to be worn at all times. For nervous and/or strong dogs a harness should be used in the early days after adoption.

Of course you have to leave your dog at home while you go to work, go shopping or other places that a dog cannot go. When your dog is new to the family routine he needs to learn that when you go out you do come back so try not to leave him too long at first. Try going out and returning after about 5 minutes at first, then 10 minutes and then longer. Most will learn quickly but do remember that they will need a toilet break and cannot last all day. Give your dog proper care and you will have a friend for life. Sometimes it helps to have two.

Potential diseases in dogs: There are three major infections affecting dogs in the UK today – PARVOVIRUS, HEPATITIS and LEPTOSPIROSIS. All should be controlled by vaccination. All our galgos are vaccinated before leaving Spain -these must be kept up to date. Please consult your veterinary surgeon.

Worming: Adult dogs should be wormed every three months against tapeworm and roundworm. However in certain areas of the UK especially Southern England and Wales it is recommended your dog is treated against Lungworm on a monthly basis – please consult your local Veterinary Practice for advice. Tick prevention is also necessary for certain areas of the UK and again we would ask you to discuss this with your local veterinarian.

Fleas: It is recommended that adult dogs are treated against fleas on a monthly basis. Many different preparations are available and some even will treat against worms – please consult your local Veterinary Practice for advice.

For more information on worms and fleas, you may find http://www.itsajungle.co.uk a useful online resource.

GENERAL INFORMATION ON MEDITERRANEAN DISEASES

All of the galgos we rescue are tested for Leishmaniasis, Babesiosis, Heartworm, and Ehrlichiosis which are diseases that occur in Mediterranean countries but are not commonly known or endemic in the UK. The tests we undertake are to ascertain whether an individual galgo is currently infected with this disease but diagnosis can be challenging and latent infections can be difficult to diagnose. The aim of this report is not to make you worry about these diseases but only to make you aware of the existence of these diseases.

Leishmaniasis

Causing agent:

Leishmaniasis is caused by the protozoan parasite Leishmania infantum, which is transmitted by sand flies of the Phlebotomus species. Dogs are the major reservoir for this infection.

Geographical distribution in Europe:

Leishmania infantum can be found in Spain in the Mediterranean coast, south coast and some central regions like Madrid, in most of the parts of Italy, being more predominant in the southern regions and Sardinia and in Mediterranean coast of France.

Transmission:

The Leishmania parasite is transmitted to the dog by the bite of the sandfly when feeding on the dogs’ blood. The most common time of the year for the sandfly to feed on the dog is from April until late September. Sandflies are weather dependent and are more predominant near water sources like rivers. The incubation period can take from 3 months to seven years. Leishmaniasis is a zoonotic disease; this means it can be transmitted to humans by the sandfly as a vector, so the dog can act as a reservoir for the parasite. This transmission can happen in countries in Southern Europe where the sandfly is present; however the clinical signs would not be like the dog’s clinical signs. Recently blood transmission has been reported and, therefore, we recommend none of our re-homed galgos act as blood donors.

Clinical signs:

Leishmaniasis can have many different clinical signs like skin lesions (scaling, hair loss and ulceration especially of the head and pressure points), abnormal nails growth, recurrent conjunctivitis, decreased appetite and weight loss, exercise intolerance and lethargy, vomiting and blood found in the stools. However, the most common ones are Epistaxis (Nose bleeds), ocular abnormalities and renal (Kidney) failure. On clinical examination enlarged lymph nodes and spleen can be observed. Renal failure due to immune-complex glomerulonephritis eventually develops and is believed to be the main cause of death in dogs.

Diagnosis:

By blood test to detect Leishmania antibodies (ELISA test); more complex tests for identification can be done like a PCR test. We recommended annual antibody testing for all our rehomed galgos.

Treatment and prevention:

If the dog shows any of the clinical signs found above and it has been in an endemic area it should be taken to the veterinarian and let the veterinarian know in which country the dog has been to. The main drugs used for the treatment of leishmaniasis are the pentavalent antimony meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime®) and allopurinol. Miltefosine (Milteforan®) is a relatively new anti-leishmanial drug that can be used for the first month of treatment in combination with allopurinol instead of meglumine antimoniate. Amphotericin B is also used but it is highly nephrotoxic (Toxic for the kidneys). These treatments are often designed to improve the dog’s condition temporarily but sometimes the disease can reoccur. The treatment does not eliminate the parasite. Keeping infected dogs where the sandfly is present needs to be thought about as a treated dog is considered as a carrier and can transmit the parasite via the sandfly to other dogs and people. In endemic countries dogs are given topical insecticides in Deltamethrin impregnated collars or spot-on drops to reduce the number of sandfly bites. A new vaccination (CaniLeash®) has been licenced in Europe offering protection against Leishmaniasis. This vaccination should only be given to dogs that test negative for diseases and will be particularly useful for dogs traveling to areas where Leishmaniasis is endemic. Trials are currently underway to test the use of this vaccine in animals previously exposed to Leishmaniasis but results are not expected for at least 5-10 years!

Babesiosis or redwater

Causing agent:

The Babesia species. A protozoa organism that parasites the erythrocytes. The most common species that causes canine babesiosis are the Babesia canis and the Babesia gibsoni.

Geographical distribution:

Present worldwide including in some parts of the UK and in Europe particularly in Southern France. In 2016 an outbreak of Babesia canis was reported in Essex with the subsequent discovery of Babesia canis infected ticks also in the area, suggesting this disease may become endemic in the UK.

Transmission:

Between animals by ticks when feeding on the dog’s blood, the longer the tick feeds the higher the chances of passing the Babesia to the dog and by contaminated instruments and needles.

Clinical signs:

The clinical findings and the severity of these can vary. The most common symptoms are pale tongue, gums and nose due to low number of red blood cells, fever, loss of appetite, lethargy, red or orange urine, enlarged lymph nodes. The most severe infections are called peracute infections and show typical symptoms of a hypotensive shock; pale membranes, tachycardia, weak pulse and depression this associated with organ dysfunction leads to coma and death. Acute infections signs are fever, anaemia, jaundice, inappetence, weakness and sometimes death.

Diagnosis:

By blood test. Directly seeing the parasite using a stain but using PCR Test is most reliable.

Treatment and prevention:

The dog should be taken to the veterinarian to get a correct diagnose and treatment. There are several drugs that can be used to treat the dog after being correctly diagnosed. These are imidocarb, and Ataquavone often in combination with an antibiotic. If the dog has severe anaemia blood transfusion should be considered. In order to prevent tick bites the dog and the dog kennels should be treated with an appropriate acaricide. A vaccine that protects the dog for 6 months has been recently developed and it is used in Europe.

Heartworm disease or canine heartworm

Causing agent:

Dirofilaria immitis. Is a filarial worm that as an adult lives in the cardiovascular system, in the right ventricle, right atrium, pulmonary artery and posterior vena cava. The final host are dogs, wild canids and sometimes cats and ferrets.

Geographical distribution:

Warn-temperature countries and tropical zones. In Europe countries like Spain and France. There have been some cases in the UK of animals who have travelled abroad.

Transmission:

Transmitted by mosquitoes of the genera Aedes, Anopheles and Culex. The female mosquito bites taking blood from an infected animal, after two weeks the mosquito carries the larvae in the mouth parts and bites another animal. The larvae develop in the host system and migrate to the heart vessels.

Clinical signs:

Heartworm is asymptomatic in the early stages of the disease. Clinical signs start when there are a high number of worms obstructing the blood flow. This causes endocarditis and dead worms in the system can cause pulmonary embolism. Heavily infected dogs suffer from loss of condition and exercise intolerance. It is common to observe a chronic cough and breathlessness.

Diagnosis:

The dog should be taken to the veterinarian where it will have a blood test +/-an x-ray and heart ultrasound done. The blood test will run two tests an antigen test to detect adult females and the Knott test which allows identification of larval stages. Occasionally these tests will be negative despite Heartworm infection.

Treatment and prevention:

Once the dog is diagnosed before dealing with the parasite the dog may need to be treated for cardiac insufficiency. Treatment is a combination of heartworm prevention treatments, antibiotics (doxycycline) and usually three injections of melarsomine over a period of 4 months. During treatment the activity of the dog must mbe restricted to avoid risk of pulmonary embolism as a result of the dead worms in the system. To prevent heartworm infection the use of oral or spot-on preparations must be used when travelling or living in endemic areas. Ideally preventation you start prior to leaving for an endemic country and for a month after visiting such an area.

Ehrlichiosis

Causing agent:

A bacterium from the Rickettsiaceae family called Ehrlichia canis. This bacterium infects dogs but other Ehrlichia species can infect humans and other animal species.

Geographic distribution:

Worldwide distributed.

Transmission:

By Rhipicephalus sanguineous tick or brown dog tick. The tick is not endemic in the UK currently although an increasing number of these ticks have been found in the uK on imported dogs. Transmission from the tick to a dog can occur within a few hours of attachment.

Clinical signs:

The clinical signs vary depending on the stage of the infection. In the acute phase the clinical signs can vary, the signs can be depression, lethargy, anorexia and pyrexia and weight loss. Specific signs are enlarged lymph nodes and spleen, occasional epistaxis (nose bleed) and petechia (blood spots in the skin or gums). In the chronic severe form, the symptoms will be the same as in the acute form but more severe. Systemic signs can be haemorrhage, shock and multi-organ failure.

Low platelets, (thrombocytopenia), white blood cells (leucopenia) and red blood cells (anaemia) are also commonly seen.

Diagnosis:

By blood test either by directly seeing the parasite on blood film analysis or, more reliably using PCR.

Treatment and prevention:

Doxycycline, for four weeks is the treatment of choice. However, elimination of infection may not occur. Chronically infected dogs can be very difficult to treat and have a very poor prognosis.

Prevention is by the use of effective tick control and avoiding tick exposure whenever possible. Any ticks found on a dog should be promptly removed and a topical ectoparasiticide that is effective against ticks applied.

There is no vaccine.

Hepatozoonosis

Causing agent:

A protozoan parasite from the Heapatozoon genus called Hepatozoon canis.

Geographic distribution:

Mediterranean Countries, Middle East, Asia and India.

Transmission:

By Rhipicephalus sanguineous tick or brown dog tick. However, unlike most tick borne diseases dogs become infected by eating the tick rather than via a tick bite.

Clinical signs:

The clinical signs vary depending on the stage of the infection. In the acute phase the clinical sings can vary, the signs can be depression, lethargy, anorexia and pyrexia and weight loss. Specific signs are enlarged lymph nodes and spleen, occasional epistaxis (nose bleed) and petechia (blood spots in the skin or gums). In the chronic severe form the symptoms will be the same as in the acute form but more severe. Systemic signs can be haemorrhage, shock and multi-organ failure.

Diagnosis:

By clinical presentation, pathological findings (E. canis invades mononuclear cells, there is a decrease in platelet number, mild leucopenia and anaemia) and a PCR blood test.

Treatment and prevention:

Once the disease has been diagnosed there are several drugs that can be used such as Doxycycline, tetracyclyine hydrochloride, oxytetracyclin and chloramphenicol. The dose and time of treatment depends on the drug used.

There is no vaccine therefore the best way to prevent the disease is by using acaricides that will prevent the tick from feeding on the dog. Remove all ticks promptly using a tick remover.

Anaplasmosis

Causing agent:

Anaplasmosis is caused by a rickettsial bacteria (Anaplasma phagocytophilum) that infects primarily dogs’ neutrophils.

Geographical distribution:

Present throughout Europe and recently identified in the UK.

Transmission:

Anaplasma is spread via the tick Ixodes ricinus – transmission occurring between 36 and 48 hours after the tick starts to feed. A recent survey in the UK found that 0.74% of ticks were infected with A.phagocytophilium.

Clinical signs

Infection is often mild or subclinical but occasionally more severe signs are seen. These include pyrexia (high temperature), lethargy, anorexia, polyarthritis (multiple inflammation of the joints), neck pain, pallor, lymphadenopathy and enlarged spleen.

These signs are due to A.phagocytophilium causing a reduction in a dog’s platelet, white blood cell and red blood cell numbers.

Signs usually occur around two weeks after the tick bite.

Diagnosis:

By blood test either by directly seeing the parasite on blood film analysis or, more reliably using PCR.

Treatment and prevention:

A. phagocytophilum is treated with Doxycycline. A 2 week course is usually sufficient although the actual required treatment duration is not known. Most dogs improve within 24-48 hours of starting treatment, although occasional supportive care e.g. intravenous fluid therapy, may be required.

Prevention is by the use of effective tick control and to avoid tick exposure whenever possible. Any ticks found on a dog should be promptly removed and a topical ectoparasiticide that is effective against ticks applied

Brucellosis

The UK has recently seen an increase in the number of dogs presenting with symptoms of Brucella canis. Brucella canis is zoonotic to humans and infected dogs pose a risk to humans especially veterinarians, when performing surgery, and laboratory staff, when handling blood or urine samples. Transmission to owners is considered low. Although human infection is rare in the UK it can be extremely severe and can lead to death. If diagnosed antibiotic therapy of infected humans is usually successful.

Causing agent:

Brucella canis is a bacteria.

Geographical distribution:

Brucella canis is present worldwide however Eastern Europe and the Middle East seem to have higher infection rates than other Europe countries. One recent study showed that the prevalence of Brucella canis in Western Europe was around 5%.

Transmission:

Brucella canis is transmitted from dog to dog by sexual contact or from bitch to pup. In addition, dogs coming into contact with reproductive tissues, discharges, or urine of an infected dog may become infected.

Clinical signs:

Infected dogs are often asymptomatic, however, they show signs related to the reproductive system i.e. infertility, abortion, weak puppies, scrotal swelling, or vaginal discharge. In addition, dogs may present with discospondylitis – inflammation of the spine cord.

Diagnosis:

Unfortunately, there is no perfect test for brucellosis. The most accurate test at present is an antibody test which needs to be sent to a specialist laboratory.

Treatment and prevention:

It is very difficult to cure an infected dog and therefore currently treatment is not recommended due to the potential risk the dog poses to the public. Euthanasia must be a consideration as positive dogs must be isolated from all other dogs and shared dog environments. In addition contact with people must be kept to a minimum.

If you think that your galgo has any of the clinical signs shown above take them to a veterinarian as soon as possible.

Click on the link below to download a PDF version of the Homing Pack.