Masay and the Rescue from Mallorca

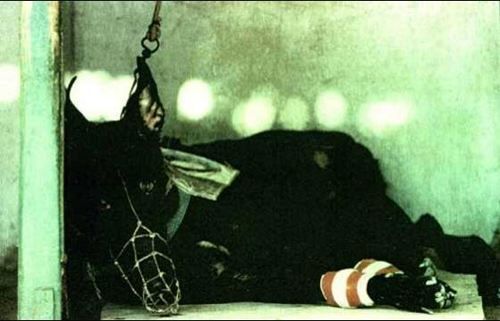

In July 1991 a horrific, heartrending article appeared in a British national newspaper about Irish greyhounds exported to Spain for racing. I knew of the scandal and had been engaged in campaigning against the export for some time. The large centre picture of Masay, a red-eyed, panting, exhausted black greyhound slumped in a cage, both legs bandaged, unable to stand up even before she was due to race, tore me to pieces. I felt someone had to go to Spain, face the Spanish and – dare I even hope- find the poor bitch and bring her to England. I had all sorts of ideas as to who should go. Was it to be a vet, a priest, a greyhound trainer? I found no-one who would go. In the meantime, I made tentative inquiries with British Airways and quarantine kennels about costs and at first it seemed all too depressing and expensive and bound up in red tape. Suddenly the miracles started to happen. British Airways offered free passage from Barcelona for three dogs worth £700; Raystede Animal Welfare Centre offered three free quarantine places worth £3000; and Willowslea Quarantine Kennels offered travel boxes valued at £300. While hardly realizing it, I personally was becoming deeply involved and reluctantly had to admit that it had to be me or no-one who would be going. I was scared out of my wits. I’d never been to Spain and spoke no Spanish.

I’d already decided that Mallorca was the only place where one stood a chance of rescuing three dogs. Even there, problems abounded. Mallorca is an island and British Airways only flew as far as Barcelona. The regulation size of the boxes was too high to fit into the cargo holds of nearly all of Iberia’s internal flights to Mallorca. Also, where would I store the boxes secretly in Mallorca? Even one box would not fit into a taxi. How would I transport and house the dogs once I’d got them? I planned, worried, sweated and wrung my hands every night for the 6 weeks coming up to the date of departure. I only slept one night in four.

Another miracle happened shortly before leaving. A Spanish lady, Marisa, whom I knew slightly at my place of work, and who had lived in England for twenty years, said she would come with me. Her strength of character, sense of humour and positive attitude were all to be invaluable.

I was encouraged the night before leaving when Marisa unexpectedly got a telephone call from an old friend she had not heard from in 9 years! And where was she these days? In Barcelona, for goodness sake, asking when Marisa would come over and see her! “I’ve got news for you,” Marisa said, “I’ll be in Barcelona tomorrow night and we are in desperate need of help!” We had the three huge boxes and nowhere to spend the night while waiting for the connecting flight to Mallorca. Fortunately, Marisa’s friend met us, sorted it all out and took us back to her flat. This bit of good luck made me feel that fate had a hand in this project and that ‘someone’ was looking after us.

Early the next morning we went on to Palma, Mallorca, not without a lot of persuasive talking from Marisa, as Iberia Airlines had decided to change their minds allowing these huge boxes on the plane. On arriving in Palma, we begged to be allowed to leave the boxes in the cargo section of the airport. It took literally hours of talking and persistence as we were passed from one official to another. They all refused to help us, saying that this simply was not done, until by chance I spied a box belonging to someone else sitting there in ‘cargo’. In the end they had to agree that the boxes could be left there after all.

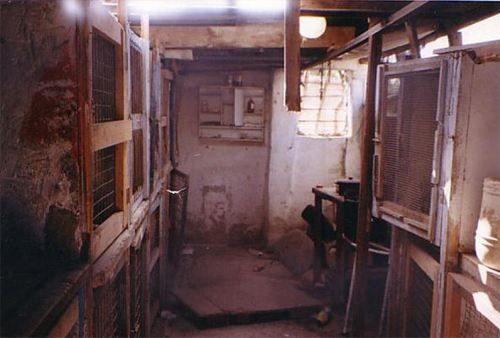

This left us free to go into Palma to find the kennels. We first found the greyhound stadium and then, like Sherlock Holmes, followed the dog-droppings on the pavement to the area where they were housed. We came across a dilapidated collection of shanty dwellings. We learned later that there were 250 dogs kept there. We rehearsed what I was going to say. My story was that I lived in Northern Spain and wanted to buy three greyhounds as pets. I figured that to offer money for the dogs was the quickest and simplest way of rescuing them. An old man called Pedro emerged from his shack with a little fawn bitch called Matilde. She would cost £35. I accepted her, made a fuss over her and then Pedro invited me inside to choose two more at £70 each. There were fifteen to twenty dogs in that dark windowless cavern, some in cages, some just tied to the wall. Most were silent and lifeless, lying on hard surfaces. In one corner was a blue bitch who trembled from head to foot in a constant state of terror. I chose her and another bitch called Linda. It was important to get away as fast as possible. Amazingly, Pedro handed me the racing documents which testified in every shocking detail how often the dogs had been running per week and how they ran through their ‘seasons’. At one worrying moment, Marisa had to do some fast talking. Pedro saw the smart greyhound collars we were putting on the dogs and asked where we got them. It hadn’t occurred to me that they were not available in Spain!

An exhausted Masay, slumped in her racing kennel before the race.

In July 1991 a horrific, heartrending article appeared in a British national newspaper about Irish greyhounds exported to Spain for racing. I knew of the scandal and had been engaged in campaigning against the export for some time. The large centre picture of Masay, a red-eyed, panting, exhausted black greyhound slumped in a cage, both legs bandaged, unable to stand up even before she was due to race, tore me to pieces. I felt someone had to go to Spain, face the Spanish and – dare I even hope- find the poor bitch and bring her to England. I had all sorts of ideas as to who should go. Was it to be a vet, a priest, a greyhound trainer? I found no no-one who would go. In the meantime, I made tentative inquiries with British Airways and quarantine kennels about costs and at first it seemed all too depressing and expensive and bound up in red tape. Suddenly the miracles started to happen. British Airways offered free passage from Barcelona for three dogs worth £700; Raystede Animal Welfare Centre offered three free quarantine places worth £3000; and Willowslea Quarantine Kennels offered travel boxes valued at £300. While hardly realizing it, I personally was becoming deeply involved and reluctantly had to admit that it had to be me or no-one who would be going. I was scared out of my wits. I’d never been to Spain and spoke no Spanish.

I’d already decided that Mallorca was the only place where one stood a chance of rescuing three dogs. Even there, problems abounded. Mallorca is an island and British Airways only flew as far as Barcelona. The regulation size of the boxes was too high to fit into the cargo holds of nearly all of Iberia’s internal flights to Mallorca. Also, where would I store the boxes secretly in Mallorca? Even one box would not fit into a taxi. How would I transport and house the dogs once I’d got them? I planned, worried, sweated and wrung my hands every night for the 6 weeks coming up to the date of departure. I only slept one night in four.

Another miracle happened shortly before leaving. A Spanish lady, Marisa, whom I knew slightly at my place of work, and who had lived in England for twenty years, said she would come with me. Her strength of character, sense of humour and positive attitude were all to be invaluable.

I was encouraged the night before leaving when Marisa unexpectedly got a telephone call from an old friend she had not heard from in 9 years! And where was she these days? In Barcelona, for goodness sake, asking when Marisa would come over and see her! “I’ve got news for you,” Marisa said, “I’ll be in Barcelona tomorrow night and we are in desperate need of help!” We had the three huge boxes and nowhere to spend the night while waiting for the connecting flight to Mallorca. Fortunately, Marisa’s friend met us, sorted it all out and took us back to her flat. This bit of good luck made me feel that fate had a hand in this project and that ‘someone’ was looking after us.

Early the next morning we went on to Palma, Mallorca, not without a lot of persuasive talking from Marisa, as Iberia Airlines had decided to change their minds allowing these huge boxes on the plane. On arriving in Palma, we begged to be allowed to leave the boxes in the cargo section of the airport. It took literally hours of talking and persistence as we were passed from one official to another. They all refused to help us, saying that this simply was not done, until by chance I spied a box belonging to someone else sitting there in ‘cargo’. In the end they had to agree that the boxes could be left there after all.

This left us free to go into Palma to find the kennels. We first found the greyhound stadium and then, like Sherlock Holmes, followed the dog-droppings on the pavement to the area where they were housed. We came across a dilapidated collection of shanty dwellings. We learned later that there were 250 dogs kept there. We rehearsed what I was going to say. My story was that I lived in Northern Spain and wanted to buy three greyhounds as pets. I figured that to offer money for the dogs was the quickest and simplest way of rescuing them. An old man called Pedro emerged from his shack with a little fawn bitch called Matilde. She would cost £35. I accepted her, made a fuss over her and then Pedro invited me inside to choose two more at £70 each. There were fifteen to twenty dogs in that dark windowless cavern, some in cages, some just tied to the wall. Most were silent and lifeless, lying on hard surfaces. In one corner was a blue bitch who trembled from head to foot in a constant state of terror. I chose her and another bitch called Linda. It was important to get away as fast as possible. Amazingly, Pedro handed me the racing documents which testified in every shocking detail how often the dogs had been running per week and how they ran through their ‘seasons’. At one worrying moment, Marisa had to do some fast talking. Pedro saw the smart greyhound collars we were putting on the dogs and asked where we got them. It hadn’t occurred to me that they were not available in Spain!

The interior of one of the hovels in Mallorca where Irish racing greyhounds were kept.

I’d heard of kennels twenty miles away run by Linda, an English lady. We hired a car, then, out of sight of the hire company, loaded in the dogs. We set out to find the kennels. The dogs were alive with fleas. On arrival, we hosed the dogs down. The fleas were crawling up my arms. The dogs had large bald patches on their rears, due to stress and the hard surfaces on which they had lain. The vet, a very kind Argentinean, came to do the necessary vaccinations, worming and health certificates for export.

It remained for us to go to the vet at the Ministry of Agriculture in Palma to obtain the final certificates for export. Nothing was easy. It was a complicated drive and finding the right office was a nightmare. One could tell that nothing much like this had been done before. Finally, our work was completed. We had only 2 more days before leaving.

Meanwhile, we visited the greyhound track and observed what went on there. Many dogs had skin diseases – I had never seen pink greyhounds before. They were bald, and many were lame before the race even started. We saw one dog have its number changed and raced for a second time that evening. In Britain dogs only race once every 7-10 days. None of the usual paddock procedures took place such as washing the sand from the dogs’ feet and eyes after racing or even giving them water to drink. We talked to several people to get as much information as possible.

Suddenly I saw Masay, the black bitch featured in the newspaper article who had inspired me to go to Spain in the first place. There she was, slumped in her pre-racing box exactly as she had been a few weeks earlier when the Press were there. The bandages on her wrists were the same. I compared her with the photo. It was she, all right. I became riveted and desperate, while Marisa tried to talk sense into me and told me to forget about it. We only had documents, quarantine places and passage for three and an airplane could only take three. But I couldn’t take my eyes off her. Marisa tried to shake me out of my obsession and suggested that we go to a flamenco show that night. I’d never heard Flamenco music before and really didn’t feel in the mood. Furthermore, it didn’t begin until 1:00am which I found excruciating as I am always up at 6:00am. Nevertheless we went.

Then something startling happened. The Gypsy singer stood up and uttered her first guttural, earthy sound, more like a raw wail from the heart than a song, and I disgraced myself by suddenly dissolving into paroxysms of uncontrollable sobbing. Never did I expect that the music would echo what I was feeling inside, that it would trigger such a disastrous response. I was quite out of control, and after half an hour of trying to get hold of myself, I had to leave.

Back at the hotel, it occurred to me, piece by piece, what I could do. Yes, I would try to get her out of the hovel and take her to Linda’s kennels. It occurred to me that Matilde’s condition was not that bad and she could wait and be sent over later when I’d sorted out more paperwork.

We were running out of time. Marisa this time took fright and wouldn’t come anywhere near the kennels. She was sure I’d be shot, going in for a second time! I went in, and stuttered away in a sort of Hispanic mixture of French and Italian. Pedro said Masay was owned by the manager of the track. I realized I would have problems procuring her. I met the manager later that evening and asked him how much she would cost. I expected him to say something like £30, as she was obviously so weak and poor, but he said 35,000 pesetas (about £200) which was extortionate, ridiculous, and obviously designed to put me off. (The Spanish only pay £50 each for the dogs in Ireland when they are fresh and young.) I gulped at this but so badly wanted her that I’d resolved not to argue about the price. How could I afford this? The cost of the trip was ruining me. That morning I had drawn more money out on a credit card and I’d grabbed a wad of notes on leaving the hotel that evening and stuffed them into a secret pocket. I was still unfamiliar with the currency so I hadn’t a clue what I had. I counted up what was there and to my amazement found I had exactly 35,000 pesetas. I immediately felt certain that I was meant to have that dog. I called his bluff and astonished him by immediately handing him the money. He could do nothing else to prevent me from having her. We hired another car and rushed her away, and then had to go through the hoop again of finding Linda’s kennels in the hills, calling the vet and going to the Ministry of Agriculture. Because of the shortage of time, we had to do things backwards. Masay had not yet been seen by the vet and vaccinated. The Ministry closed at lunchtime for the day so we went there first and submitted the paperwork, but in desperation I handed the Ministry vet another dog’s paperwork and hoped and prayed that he wouldn’t see that the colour of the dog didn’t tally. I distracted him by keeping him talking. It worked. He signed it. We’d done it.

Afterwards, we took Masay to the vet and the formalities were properly carried out. One slight hiccough was that I thought she ought to be tested for Leishmaniasis as she was in poor condition. If she had it, she would be euthanised in quarantine and the trip would have been wasted. Thankfully, the test came back negative. We had finished.

The next morning we had to get up at 4:00 am to get the dogs to the terminal. But a minor disaster struck. I had lost my memory! Yes- I awoke quite disorientated and didn’t even know which country I was in or what I was doing with these dogs! The stress of the last six weeks had finally caught up with me. Marisa took over while I tried to appear sane and we got the dogs into their boxes and checked them in for the internal flight to Barcelona. I drank pints of coffee and finally after five hours, thankfully my wits returned, as we landed in Barcelona.

From then on, British Airways, bless them, took over and apart from being struck twice by lightening on the flight back, we landed safely at Heathrow, with the quarantine van waiting on the tarmac.

The dogs did well in quarantine and were finally homed to loving caring owners. Matilde arrived a month later.

The bad publicity I gave to what I had seen caused the World Greyhound Federation to suspend the trade between Ireland and Spain for five months pending an inspection of the three greyhound establishments in Spain, and Mallorca’s kennels were ordered to close. New kennels were built at a very inconvenient site inland.

The dogs were still kept in cages without bedding, air-conditioning, piped water or a proper electricity source. Much work still needs to be done. I went to Spain 10 more times to all three tracks and kennels, taking in many suitcases of veterinary equipment, liniments, bandages, instructive videos, etc. and worked in the kennels de-infesting the dogs and dressing their wounds. I’ve managed to get 25 dogs to England , Germany and Switzerland to loving caring homes.

Masay at home in Norfolk

Dear Masay went to a lovely home in Norfolk. After two years there she tragically did develop Leishmaniasis after all, as it was latent. She bore her illness so bravely but was finally euthanized in November 1994.

She was one of those special dogs who seemed wise and aware of what she represented and instigated.

Anne Finch

Written for USA publication: Greyhound Tales; True stories of Rescue, Compassion and Love.

Ed.Nora Star. 1997.